Hacking the Blues Guitar

This page is part of the Hacking the Blues series. This page is still a "work in progress"...

Contents

Introduction[edit]

Is it possible to apply Hackerspace principles to learning an instrument? Can this be made into a learning project where others can benefit from each other? Well, I guess it is worth giving it a try.

You will notice that different to most guitar courses this is not designed to quickly give you some simple song to play along for a quick success, rather it will try to explain everything as good as possible (and necessary) before given you an exercise to learn to use it.

Of course, this will not turn you into a master blues guitar player – that requires many years of exercise – but it will be enough to get started, have some fun and see if you like to learn more.

Prerequisites[edit]

- Guitar (electric or accoustic), tuned (!)

- Beginners knowledge, e.g. chords like A, D, E, etc.

- Someone to play with (optional)

Time required[edit]

- A week to learn, a lifetime to master

About the Blues[edit]

Blues is a style of music that originally developped in the 19th century in the afro-american population of the U.S. by mixing elements of European and African music styles. Blues is the rock-solid foundation on which popular styles like Rock'n'Roll, R&B, Rock, Soul, etc. are built. Even most AC/DC-songs are essentially Blues (just with a lot of overdrive).

There is a pretty good Wikipedia article about the the Blues, but one can't really explain music in words. If you are reading this, you are probably already fascinated by musicians like Eric Clapton, Jimi Hendrix, B. B. King, John Lee Hooker or - heck, why not - even Gary Moore or the Blues Brothers. If not, click on the links to watch them play on YouTube.

Ready to become a Blues Man (or of course Blues Woman) yourself? Before you grab your guitar, I'm afraid we need to do a bit of theory first:

Lesson 1 - The Blues Progression[edit]

Chord progressions[edit]

If you ever wondered how musicians can simply play along with each other although they never heard the song before, here's how: they actually always play the same pattern of chords (called a "progression") and just move it through the scale (and possibly modify it a bit).

With the Blues, the chords that belong together - apart from the main "key" of the song (which in music theory is called the "tonic" or first), there is the fourth (called "subdominant") and fifth (or "dominant").

OK, that sounds complicated - it isn't. Here's an overview for a few selected keys, please read this from top to bottom, i.e. for a Blues in "E", the sequence is E-A-B:

| Key / Tonic (I) | E | F | G | A | B | C | D |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subdominant (IV) | A | B♭ | C | D | E | F | G |

| Dominant (V) | B | C | D | E | F♯ | G | A |

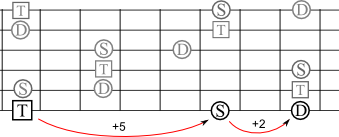

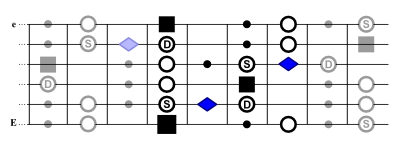

Still sounds complicated? Let's have a look at where we can find the tonic ('T'), subdominant ('S') and dominant ('D') on the guitar:

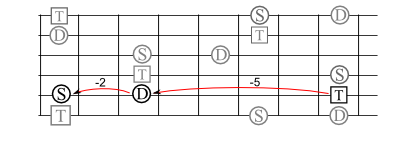

How to read this: once you have located the tone corresponding to the key of the song on the guitar, you can find the subdominant five frets down on the same string, and the dominant two more down from there.

Of course, mathematically minded people will quickly see: as there are 12 different notes, and if the dominant is seven frets down from the tonic, you can also find it five frets up from the key. Actually, you could already see this on the fretboard above (look at the A-string), but here it is again with highlights:

So you can also think of the three main chords as being five notes away from each other with the key note (the "tonic") right in the middle.

And that means it doesn't matter in which key you are playing, the keys you are looking for are always 5 frets down and 5 frets up from the key note. For example, if you play in A (5th fret on the E-string), the subdominant is D (5 + 5 = 10th fret) and the dominant is E (5 - 5 = 0th fret = empty string, or 10th + 2 = 12th fret).

Knowing this, you can forget the progression table again, all you need to remember is where to find the tonic - preferably on the E-string.

In case you don't remember that, please see this table:

| Fret | 0 (empty) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Note | E | F | F♯/G♭ | G | G♯/A♭ | A | A♯/B♭ | B | C | C♯/D♭ | D | D♯/E♭ | E | etc. |

And, yes, this table is the one you need to learn by heart. SRSLY.

Exercise[edit]

You know now how musicians know which chords to play if they are told: "Blues in A".

- name the chords you need to play in "Blues in E", a "Blues in D" or a "Blues in B♭"?

More information[edit]

Of course, there is another approach to learning this, called the Circle of Fifths. Have a look at it, maybe you like this better (just make sure you have "Major / Ionian" mode selected).

12-bar Blues[edit]

There are many ways how the chords of the Blues progression can be played, but the most typical form is the "12-bar Blues" pattern, where the following pattern of 12 bars is repeated throughout the song:

| Tonic (I) | Tonic (I) | Tonic (I) | Tonic (I) |

| Subdominant (IV) | Subdominant (IV) | Tonic (I) | Tonic (I) |

| Dominant (V) | Subdominant (IV) | Tonic (I) | Dominant (V) |

Agreed, this is all very abstract. Let's see how that looks in the key of 'A':

| A | A | A | A |

| D | D | A | A |

| E | D | A | E |

The last, 12th bar is called the "turnaround". This is where the tension built up during the rest of the pattern is released and somehow "rolled back". It often features a change in rhythm as well; A good drummer will at least mark the end of this bar (and hence the sequence) with a cymbal crash or a drum roll or something similar. This makes it easier to find into a song without having to count the bars from the beginning...

Simple as it is, this pattern is the basis for the vast majority of Blues, R&B, Blues Rock and of course Rock'n'Roll songs. Learn this and you will be able to play along with a lot of different songs.

You may think that such a strict pattern is quite restricting for musicians, but any music-collection holds the proof that an endless stream of creativity can be added on top of it. Think of it this way: this pattern makes sure that you don't have to waste time explaining your band members how they have to play, so you can focus of your guitar solos and creative lyrics writing.

In other words, think of it as a design pattern. As all design patterns, the 12-bar Blues pattern has its limitations, but it has proven to be useful in many situations.

Just for the record, it is also good to know some common variations of this pattern:

Quick change

Some musicians consider the first four bars without any tonal change as too long and boring, so they play a variation that is known as the "quick change":

| Tonic (I) | Subdominant (IV) | Tonic (I) | Tonic (I) |

| ⋯ | |||

Or for the example in the key of A this translates into:

| A | D | A | A |

| ⋯ | |||

All you need to remember is simply that if there is some odd tonal change just one bar after the drummer hit the crash, you are probably in a "quick change" scheme ...

No turnaround

For some songs, there is no need for a tonal "turnaround" needed, so the last four bars are simply played as follows:

| ⋯ | |||

| Dominant (V) | Dominant (V) | Tonic (I) | Tonic (I) |

Once again, translated for the key of A:

| ⋯ | |||

| E | E | A | A |

This variant is often used in combination with the "quick change" variation mentioned above.

24-bar Blues

A 24-bar Blues is effectively just a 12-bar Blues where each bar is duplicated. Quite simple, really - just count to eight instead of four, etc.

Using sevenths

Blues guitarists love sevenths. Seriously! They will try to sneak them in whenever they can, often without telling the piano player (who hates them) or the drummer (who doesn't care).

At least the very last bar is very commonly played as a seventh, other candidates are the fourth and eight - but if nobody stops them, Blues guitarists may well try to play a seventh in every single bar of the scheme.

Here once again the 12-bar scheme with the usual suspects marked as sevenths:

| A | A | A | A7 |

| D | D | A | A7 |

| E | D | A | E7 |

At least you know now why the 12-bar scheme is usually presented in a 4×3 table: it's so the seventh chords align neatly at the end of each line ;-)

Exercises[edit]

Please play the following YouTube video in a new window:

Please take your time to complete the following exercises. Even if you think that they are easy and you want to move on - it is better to spend 5 minutes repeating something you think you already know than to being stuck later because you missed something you should have learned earlier...

- Please count the beat to know at any time at which section of the 12-bar scheme you are in the song; please speak the key out loud together with the count (like: "A - 2 - 3 - 4 / D - 2 - 3 - 4 /", etc.)

- Take your guitar and play the base note on the E-string (hint: A is on the 5th, D on the 10th, E on the 12th or on the empty string [0th])

- Search YouTube for more Blues backing tracks in A and try to play along.

- Why not try your luck with Blues backing tracks in other keys? It's not so hard ...

Other bar schemes[edit]

Not every song writer lets him or herself being limited by the 12-bar Blues scheme, so you may encounter some other patterns, like 7, 13, 15, 25 or other counts.

The most popular of the "other" schemes, however, is the 8-bar scheme. This is how it looks like for the key of A:

| A | E | D | D |

| A | E | A | E |

This is used in one particularly famous "traditional" Blues called "Key to the Highway", played like this:

A E D D7

I got the key to the highway; I'm booked out and bound to go,

A E A E

I'm gonna leave here running; ain't coming back no more

...

Have a look at Eric Clapton playing it live (and try to count the bars as an extra exercise!)

And here's a really weïrd (literally) scheme used by Donovan in his awe-inspiring song Season of the Witch (watch on YouTube):

| A7 | D9 | A7 | D9 |

| A7 | D9 | A7 | D9 |

| A7 | D9 | A7 | D9 |

A7 D9 A7 D9 When I look out my window, many sights to see. A7 D9 A7 D9 And when I look in my window, so many different people to be. ...

If any proof was needed that a great song doesn't need a complex chord progression, here it is.

Oh wait... that's not a proper Blues you say? Well, maybe you're right, but maybe you're not.

More Information[edit]

- Wikipedia article on Twelve-bar Blues

- Standard Blues Progressions - a more academic approach to different Blues progressions

Lesson 2 - Improvising on the Blues scale[edit]

We all know, the reason we all bought a guitar in the first place was not to play chords (or the bass tones as in the exercise above) but to play cool guitar solos.

Blues solos as actually even more fun than you think, as they are usually based on some improvisation. That means, you don't think much about what to play but just "let it roll". Before you can do that, you need to know which tones fit to the key you are playing in. For this, you need to learn the Blues scale:

The Pentatonic scale[edit]

The "framework" around which the Blues is built is a pentatonic scale (precisely the minor pentatonic scale). We can consider the notes of the pentatonic scale the "safe notes", as they will always fit any song (as long as they are in the right key).

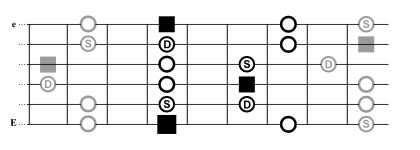

The following picture shows you the position of the notes from the pentatonic scale on the guitar. The squares indicate the location of the base notes, the circles the other tones in the pentatonic scale. Ignore the greyed out notes for now, we'll come back to these later...

Please memorise the typical "K"-shaped pattern, starting from the base note on the "E"-string. This is the first of a series of pattern, and definitely the most important one.

While the pentatonic scale has the advantage of being "safe", i.e. all tones fit well to each other, it's also a very boring scale - there is nothing here that could create a bit of tension or dissonance. We will learn some extra notes that do just that in a short while, but before we move on, please exercise this pattern well:

Exercise[edit]

- play the pentatonic scale up and down a few times for different base tones, e.g. for A starting on the 5th fret, for D on the 10th, etc.

- Please make sure to always start and end at the base tones (the squares); please ignore the greyed out notes for now.

- For example, you could play this:

A or D

T |--------------------|--------------5--8--| |--------------------|-------------10-13-|

|--------------------|--------5--8--------| |--------------------|-------10-13-------|

A |--------------------|--5--7--------------| |--------------------|-10-12-------------|

|--------------5--7--|--------------------| |-------------10-12--|-------------------|

B |--------5--7--------|--------------------| |-------10-12--------|-------------------|

|--5--8--------------|--------------------| |-10-13--------------|-------------------|

- Please play this back and forth until you know this pattern by heart.

Blue notes[edit]

Probably the most distinguished feature of the Blues (and actually the feature that gave him its name) are the blue notes. This is remarkable, as nobody actually really knows what a blue note is. All we know is that the Blues probably inherited them from its African ancestry, and that you actually can't really find them on your fretboard.

The original blue note has to be tuned in a way that our European instruments were never designed for. So when the Blues evolved, the first musicians had to find some workaround for this, and what they came up with changed the way we understand music ever since:

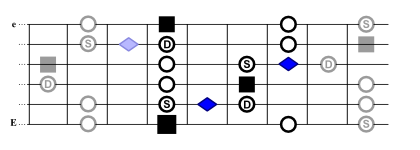

In short, since you won't be able to hit the "proper" blue note anyway, you have to play the next best note (marked as blue diamonds in the following chart), but you have to play it dirty, i.e. you bend it, slide in or out, or do a strong vibrato; whatever you like, just don't play it straight and clean.

You should note that the blue note is always located between two valid and "safe" pentatonic notes. This makes it very easy to bend, stretch or slide in and out from the blue notes.

Exercise[edit]

- Try some slidings, hammer-ons and bendings to play the blue notes.

- Play the scales up and down a few more time, as in the previous exercise, but this time try to add some blue notes.

- for example, you could play it like this:

A

T |---------------------|-----------------5--8-|

|---------------------|-----------5--8-------|

A |---------------------|--5--7-b8-------------| b7 = bend previous note up until it sounds like fret 7

|---------------5--7~-|----------------------|

B |--------5-6s7--------|----------------------| 6s7 = slide from the 6th into the 7th fret

|--5--8---------------|----------------------|

You will notice that what was a rather dull sequence before, now has got a nice "bluesy" feel to it. Congratulations, you have just unlocked the "Blues Man" achievement batch.

More information[edit]

- If you have problems to make the bends, slides or hammer-ons sound good, please click on the links to get more detailed instructions.

Notes from other scales[edit]

Of course, not everybody is satisfied with the limited choice of tones that the pentatonic scale plus blue note has to offer. There are countless ways to add more notes, or to use completely different scales altogether, but the most common approach is to add some notes from the major scale to the Blues scale. In particular, this is a common approach in the Blues Rock style.

Please see the following fretboard chart. The additional notes are marked as small black dots:

The Entire Guitar Blues Pattern[edit]

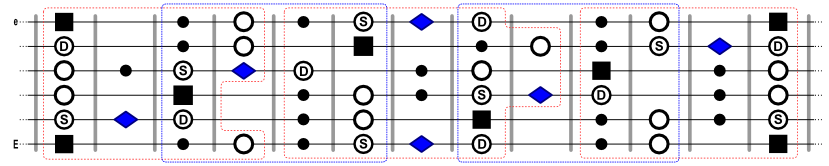

Now we have all the information needed to draw a full fretboard with all the Blues tones marked out on it:

This looks a bit intimidating at first, but but try to exercise the different hand positions (market by blue and red dashed lines) and you will find it is actually really easy.

At the very least, you should learn the following patterns:

Fourth Hand Position[edit]

This actually looks very similar to the first position we learned earlier, so it's probably best to just learn the differences:

*image*

The reason this one is so important is that this can be used to change from Tonic (I) to Subdominant (IV) without changing the hand position.

So, for example, if you play in the key of A (using the first pattern, i.e. in the fifth fret), you can change to D by moving the same pattern into the 10th fret, or you can continue in the fifth fret by using this pattern.

Third Hand Position[edit]

Likewise for the Dominant (V), simply use this pattern:

*image*

Again, it is so similar to the first pattern that it is probably easiest to just focus on what is different rather than learing the entire pattern by heart.

Sliding Pattern =[edit]

At some point, you will start to feel that the above pattern (for obvious reasons they are also called "box" pattern) rather restrictive and uninspiring. The following is an example for a much wider pattern that you can use to extend a solo over the entire (well, almost) fretboard – or at least, it should give you the inspiration to try and find your own patterns:

*image*

To train this pattern, please try to play the following scale back and forth until you feel confident about it:

A

T |------------------------------------10-s12-|

|-----------------------------8--10---------|

A |--------------------5--7-s9----------------|

|--------------5--7-------------------------| s = slide into this fret

B |-----3--5-s7-------------------------------|

|--5----------------------------------------|

Links[edit]

- All Guitar Chords - lots of guitar information on chords, progressions, etc.